“I want you to see us”: A dialogue on the tensions of the Black Body being seen in the American Theatre

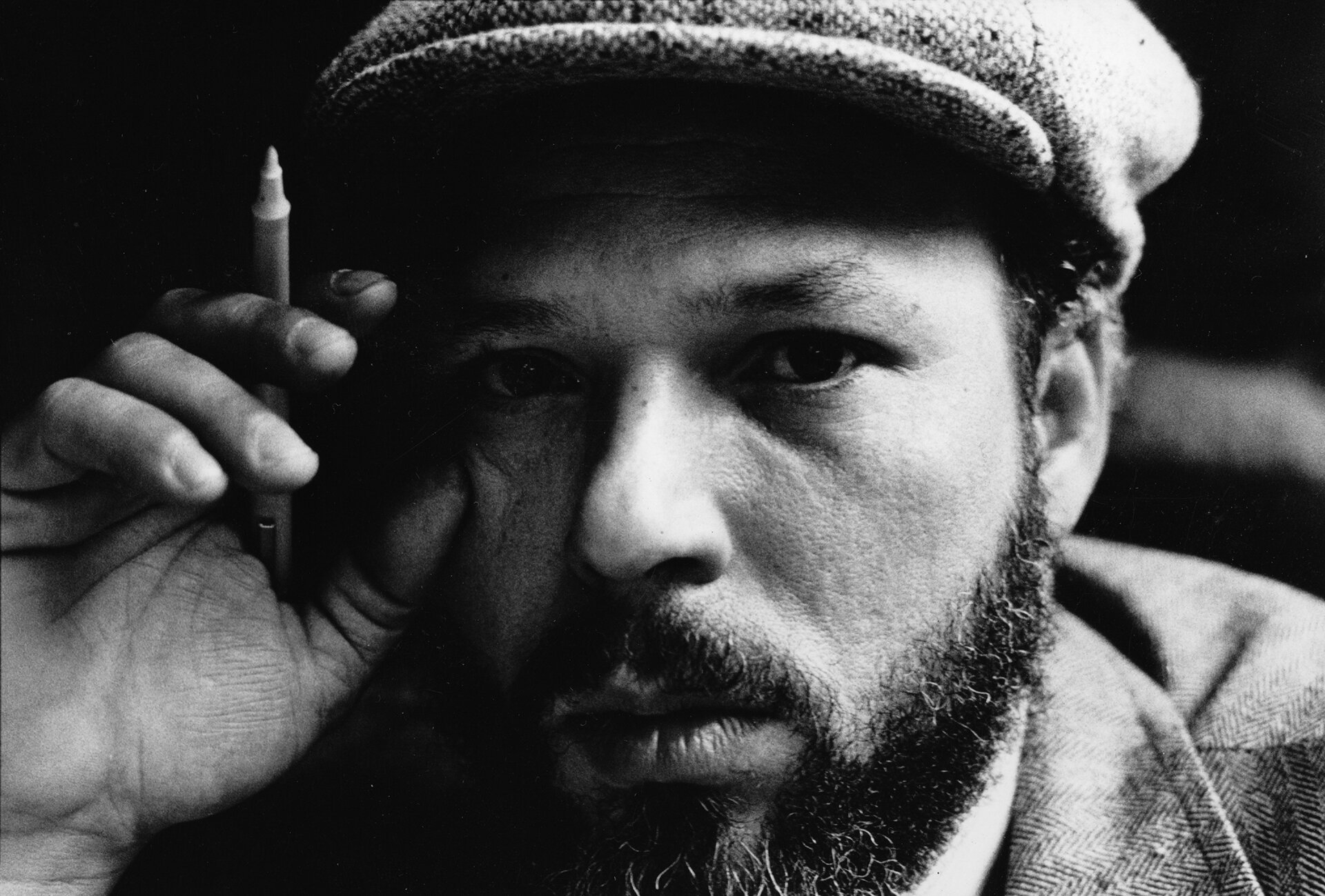

August Wilson, Poet & Playwright

Black theatre as of the 21st century is surrounded with conversations and interventions to revive its legacy. Black theatre, according to many critics today, is in peril. When the notions are brought forth one has to consider the speaker and the formation of the conversation. With the construction of the non-profit structure for theatres, Black theatres have been struggling to be viewed favorably in order to receive monies from granting organizations like Ford, Doris Duke, and Rockefeller Foundations. In this American society, the practice of theatre is not formed simply around the practice of art but mostly in relation to an economic contingent. It is quite simple. If one wants to receive money from a group, one has to be seen by that group making oneself visible is a supposed necessary practice. When economic value is given to a theatre group and the theatre group is then projected to a status of visibility it allows for an assumption that the art practices of the theatre are of value. But how does acquiring economic wealth and grants equate to value within an art practice?

In 1996 August Wilson wrote, The Ground on Which I stand, which was a response to the low numbers of Black theatres and the conversation around color blind casting. Wilson, an artist from Pittsburgh, began his career as Black poet in Saint Paul and wrote a piece, Black Bart and the Sacred Hills that was produced at Penumbra Theatre- the resident Black theatre space. The play would not be one that was regarded as his best, but opened a door of thought for more of his plays to follow. He would go on to create a ten-play cycle chronicling the stories of a group of Black people, all set in Pittsburgh, PA. Wilson found many artistic homes but Lloyd Richards, Director of the Eugene O’Neil and Yale School of Drama, provided a space of possibility that took Wilson to another level. In 1996, Wilson is a highly regarded playwright and thinker and he is standing in front of artists-professional theatre makers-administrators challenging the practices of theatre that have allowed for the absence of Black theatre’s voice within the American Theatre conversation. Wilson is contesting a notion that Black artists should have to just participate at larger regional theatres and is calling for the building of more Black theatre institutions. In Black theatre history in the Unites States, space has always been a concern due to racist practices of displacing black artists due to economics, class, and color of skin. Wilson points directly to this tension when it is suggested that the concept of color-blind casting can be used in regional houses. This is defined by a notion that any artist regardless of color can play a role. Wilson refuses to accept this thought and states:

“I want you to see us” (Wilson)

I want you to see us. How many Blacks have uttered these words whether at a podium or in the inner psyche of our minds. Who does Wilson want to be seen by and why? What will the view provide? What will it cost? Will the new eyes promise a potential for some sort of transformation? In order to fit within an institutional structure one has to be seen. To be seen is to be viewed, acknowledged, able to digest that one is seen, able to process the accepted view from an outside eye. Wilson asking to be seen by large regional theatres with majority white male artistic leadership is a call to a deeper issue. Maybe Wilson feels that if ‘We”, Black theatre is seen, then it will be viewed as human- as real.

“I want you to see us”

As if the act of seeing will provide a new response or a consciousness building to erase the images seen or assumed to be seen in the past. Without an offering of an everyday practice, to ask someone to be able to see you- all of you-acknowledge you as a person valuable enough to have breath.

“I want you to see us”

There is also an assumption that the “I”, August Wilson, can stand for the “us”. But who is the “us”? Is it Black folk in New Haven that have never seen a Wilson play-is it the affluent Blacks that believe theatre is a space to validate economic standing- is it the kid in his first Black theatre class- is it the young Black playwright trying to produce his play? Who is the “us” and can that be defined? What if I don’t want to be seen? What if I don’t want to be seen/dissected by eyes that I had to ask to look at me? What if I don’t believe in what you view as a Black theatre- can you/ are you standing for me?

The Ground on which I stand is a hot bloody mess filled with years of aching heart ache- unanswered questions-extreme joys and utter pain. The Ground on which I stand is a blade in the side of my right eye while the most beautiful breeze reminds me of my childhood. The Ground on which I stand literally doesn’t want me and adores me. The Ground on which I stand is holy- Alive- Real- Fake. The ground is the ground.And I am that I am.

I long for the dark/ to not be seen/ to wander into spaces and crevices no one ever could ever wander into/ I long for the dark abyss/ within/ within and underneath these streets of glitter and fame/ I long for more than the temporal light from the street lamp/ I long for the internal light that I can only see once I’ve explored my innermost darkness/ I long for the blinding dark/ light that is beckoning me to remember so I can travel through any space I may choose (Washington).

Going Dark

“I want you to see us”--- what if Wilson’s statement shifted to:

“I want to see us"

“I want to see me”

The notion of rejecting the view of the exterior to activate an inner excavation is a thought that has plagued the more commercially successful Black artists of the 21st Century. What would it mean for an artist to search within him/herself for the answer to the nagging questions of sustainability, aesthetic, art consumption, and even more complex: How to exist in an American space with a sane presence? What if August Wilson was grappling with the thought of “wanting to see himself” versus “being seen”?

Would he be standing in front of this audience at the TCG conference in 1996 or would he be somewhere else? Is there a way to want to explore “the inner” while being an active part of systemic theatre practices which deem you to be seen? Is there a way to strategize how one can be visible and invisible (attentive to the self), at the same time?

Drawing fromartists of the Black Arts Movement, the concept of ‘darkening’ up philosophy and art practices was viewed by Black artists such as Amiri Baraka, Larry Neale, and Barbara Ann Teer as a tactic to off-set the racist and oppressive practices performed by the American Theatre Institution. Instead of forcing its way into the structural walls of theatres in the sixties, artists began to create their own space to create art which would ‘look into black skulls’ as Baraka proclaims (Baraka). Neal begins in his seminal essay on the formation of the Black Arts Movement that ‘the Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community” (Neal). And Teer, founder of the National Black Theatre in Harlem advocates: “We must begin building cultural centers where we can enjoy being free, open and black, where we can find out how talented we really are, where we can be what we were born to be, and not what we were brainwashed to be, where we can literally ‘blow our minds’ with blackness (Teer). These three artists represent only a portion of the formation of philosophy of the Black Arts Movement and it is important to note that Wilson claims to be a descendant from this legacy of thought. Wilson speaks the words of “The ground on Which I Stand” to incite and expose the importance of Black culture and Black art but I believe his chosen practice of delivery (TCG Conference) does not serve the desired communal thoughts around the Black arts movement.

Wilson sets himself up in a space that is isolating, outside of the Black community, to lobby to a group of power brokers the viability of Black arts and even deeper, the rationalization of the importance of the Black body in space in America:

“There are some people who will say that Black Americans do not have a culture- that cultures are reserved for other people, mostly notably Europeans of various ethnic groupings, but Black Americans are Africans, and there are many histories and many cultures on the African continent” (Wilson).

Wilson continues in his speech by detailing his own life growing up in Pittsburgh analyzing the relationship between Whites and Blacks in society and how this interaction stabilizes one group and forces the other into positions of power therefore re-establishing the binary of oppressor/oppressed. The liberators of the White American allows for the practices of whiteness to become institutionalized because it is a philosophy that is centered and now a leading force in the American Theatre engine. He states, ‘The economics are reserved as privilege to the overwhelming abundance of institutions that preserve, promote and perpetuate white culture” (Wilson ). But what ground is Wilson standing on? Who is on that land? And who owns it?